Sunday, February 18, 2007

The Flathead Valley

The one point of interest in Hungry Horse that I can find is the Hungry Horse Dam, and I drive a couple of miles steeply uphill to find it. The times being what they are, this is as close as I can get to it, and the clouds don't help either. There's boating and fishing and camping around the lake, but I do none of these, just wind back down through the pine forest and canyon, make a left on the highway, and head toward Kalispell and Missoula.

The one point of interest in Hungry Horse that I can find is the Hungry Horse Dam, and I drive a couple of miles steeply uphill to find it. The times being what they are, this is as close as I can get to it, and the clouds don't help either. There's boating and fishing and camping around the lake, but I do none of these, just wind back down through the pine forest and canyon, make a left on the highway, and head toward Kalispell and Missoula. The road runs along the Flathead River through a gap called Bad Rock Canyon, where there's another one of those point of interest signs written like a goofy parody of Zane Grey. It explains, in a tone that undermines its credibility, that the canyon's name comes from the spot where the Blackfeet held off the Flatheads in a series of raids and reprisals. (Judge for yourself here. Lord, the things you can find on the web.)

The road runs along the Flathead River through a gap called Bad Rock Canyon, where there's another one of those point of interest signs written like a goofy parody of Zane Grey. It explains, in a tone that undermines its credibility, that the canyon's name comes from the spot where the Blackfeet held off the Flatheads in a series of raids and reprisals. (Judge for yourself here. Lord, the things you can find on the web.) Anyway, it's a pretty road for a few miles, but abruptly we roll out of the mountains onto a flat plain and into Kalispell, which is the major commercial center in these parts, and save for a couple of blocks of old-fashioned downtown is one of the least appealing places I've seen to date: One big box store after another, lining the highway south of town, punctuated by signs advertising new housing developments where you can live the American dream in the glorious, wide open spaces of the wild west. Or something. It reminds me of how a professor of mine at Kenyon once described the similar landscape of Mount Vernon: "If it was a mindless development process, as it sometimes appears to be, that's really sad. If it was not a mindless process, if some group decided that this is their vision ... that's even sadder. I'd rather believe in chaos than in that."

Anyway, it's a pretty road for a few miles, but abruptly we roll out of the mountains onto a flat plain and into Kalispell, which is the major commercial center in these parts, and save for a couple of blocks of old-fashioned downtown is one of the least appealing places I've seen to date: One big box store after another, lining the highway south of town, punctuated by signs advertising new housing developments where you can live the American dream in the glorious, wide open spaces of the wild west. Or something. It reminds me of how a professor of mine at Kenyon once described the similar landscape of Mount Vernon: "If it was a mindless development process, as it sometimes appears to be, that's really sad. If it was not a mindless process, if some group decided that this is their vision ... that's even sadder. I'd rather believe in chaos than in that."So it's a relief when Kalispell peters out into fenced-in prairie at the northern end of Flathead Lake. At the advice of Big John from the Two Sisters cafe, I take the longer route around the east side of the lake to avoid construction on the main road. The route sends me through thirty or forty miles of piney woods and little towns geared to fishermen and boaters and horse types. It's a pretty day for driving and a straight, flat road most of the way, with cows and horses about and mountains on either side.

In the early afternoon I switch off the iPod and turn on the radio to catch the Dodgers' game. I've listened to a lot of baseball on this trip, probably too much; I haven't made any progress through the ten gigabytes of songs I'm carrying with me. On just about any given night I can dial into an east coast game and a west coast game, and on a weekend three. The Sunday night game on ESPN radio has been my calendar, and has probably led me to log a lot more miles on Sunday evenings as I realize another week has been whittled away in some place that's not my destination.

In the early afternoon I switch off the iPod and turn on the radio to catch the Dodgers' game. I've listened to a lot of baseball on this trip, probably too much; I haven't made any progress through the ten gigabytes of songs I'm carrying with me. On just about any given night I can dial into an east coast game and a west coast game, and on a weekend three. The Sunday night game on ESPN radio has been my calendar, and has probably led me to log a lot more miles on Sunday evenings as I realize another week has been whittled away in some place that's not my destination.A good baseball announcer can be the best of company on a back road. The problem is, the number of good baseball announcers seems to be on the wane. I like the pair on ESPN, and their work benefits from the lack of interest in a home team. And in Cleveland, Tom Hamilton yells too much but is otherwise genial and fair; and he has a fine partner Mike Hegan, an ex-first baseman who grew up in Cleveland watching his dad play there but had the sense to play for better teams when he grew up. So I listen to them a lot, of course, but the team is going nowhere this year, and driving around this part of the country has made me feel significantly more embarrassed and disappointed in their choice of "mascot."

Around the dial, though, too often the choice tends to be between shills on the one hand, and bores on the other. Or, in the case of the Tigers, both at the same time, and this is especially sad to someone who used to dial up WJR on a summer night just to hear Ernie Harwell say of a hitter, "He stood there like a house by the side of the road," even if it was usually my guy doing the standing.

But in the summer of 2006, there's still Vin Scully. He was in the background of my evenings for most of the three summers I spent in Los Angeles, and almost made a Dodgers fan out of me. And now in the age of satellite radio, I dial him up just about every chance I get, because someday the guy who was on the radio during Brooklyn's World Series win is going to decide he doesn't need to spend half the year going to ballgames anymore, and that'll be that.

It's a quirk of the schedule, a noon game, that puts Vin in the car with me headed down highway 35 and US 93, past a sign for a ghost town that I elect to skip and a large Hereford advertising a mini-mart and wildlife gallery. I have to stop for gas, and check out the gallery while I'm inside paying and purchasing snacks. From what I can tell, it consists of reproductions on black velvet. The Hereford is considerably more impressive.

It's a quirk of the schedule, a noon game, that puts Vin in the car with me headed down highway 35 and US 93, past a sign for a ghost town that I elect to skip and a large Hereford advertising a mini-mart and wildlife gallery. I have to stop for gas, and check out the gallery while I'm inside paying and purchasing snacks. From what I can tell, it consists of reproductions on black velvet. The Hereford is considerably more impressive.Back in the Element with Vin. There are certain actors - Morgan Freeman is one; William B. Davis of The X-Files is another - whom I especially like because of the way they seem to sing their lines. It doesn't matter whether anyone talks that way; it's beautiful and interesting and, at its best, truer than realism. So Vin Scully. He rarely yells, not even with the Dodgers on a hot streak that up to today has them winning 17 of their last 18 games: just lifts his pitch a couple of tones, elongates his words, and sings the delight of 48,000 fans to you in a way that trusts you'll get it without him hollering at you what you're supposed to feel.

He's like Freeman and Davis, but more, because he's making it up as he goes along, reading the score in front of him and then improvising from there. He stitches pet phrases into the fabric of the action; tells an old story from the days at Ebbets Field and in the middle of it lands hard on the word "whacked!" like it's his index finger dropping on A above middle C, as Jeff Kent laces a double down the line. He's one of the great jazzmen of the last half-century, and I mean that literally.

Things get a bit confusing as I get close to Missoula, and the next thing I know I'm on I-90 for the last few miles into the city. I exit downtown and head toward the University cross the Clark Fork in hopes of finding Dave.

Friday, February 16, 2007

Hungry Horse

If I'd wanted to see a bear, apparently I could have just gone across the river to Maplewood, New Jersey. And now we return you to the fictionalized present of the blog.

My intent is to find a hotel near West Glacier, which is a commercial center of sorts just outside the park itself, the better not to be whizzing past scenery in the dark. I pass a billboard for a brand new Super 8 a little further down the road, and after a day of hiking after a night of camping, itself preceded by a night in the Element, and no showers in between, a brand new Super 8 hotel sounds pretty good. But the clerk at the Super 8 gives fairly sneers at me when I ask if there are rooms. So I turn around and drive back to a town called Hungry Horse.

I hate to disillusion you, but Hungry Horse is not quite as charming and rustic as you or I would like it to be. It is, in truth, surrounded by spectacular pine forests covering steep mountainsides. No wooden sidewalks are to be found, however, and although there are saloons they do not seem to have piano players and dancing girls in petticoats. No gunfights break out on the main street , which is also the only street, while I am there, and I see no horses, whether hungry or fully satisfied. In fact, this pretty much sums up what I see in Hungry Horse, except that I do not see the Tamarack Lodge, and I end up driving across the town line into Coram to spend the night.

In Coram I pull up to one little motel and ring the bell, and when the clerk comes to the door he reminds me of Jack Nicholson in "The Shining," only without the mustache and all that mental stability. So when he says "Just a minute," I decide to use the time wisely by getting back in the car and driving rapidly out of the parking lot and up to the next little set of tourist cabins up the road.

In Coram I pull up to one little motel and ring the bell, and when the clerk comes to the door he reminds me of Jack Nicholson in "The Shining," only without the mustache and all that mental stability. So when he says "Just a minute," I decide to use the time wisely by getting back in the car and driving rapidly out of the parking lot and up to the next little set of tourist cabins up the road.

The door there is opened by a woman so impossibly sweet and slow that I realize I've locked myself into this place before the words "Do you have any rooms?" can come out of my mouth. She does have rooms, and invites me into a tiny reception area, lit by one table lamp, where every inch of wall space and flat surface overflows with Christian imagery or iconography or proselytizing pamphlets. It takes her about a minute and a half to find the registration form and enter the date, during which time I study the stack of bibles on the counter. Am I meant to take one with me back to my room? Will she tell me to be sure to take one? Will there be trouble if I don't?

She asks for my identification and credit card, and I hand her my license, and she comments of course on how far from home I am. She also notes that my name is Christopher. "What a nice name," she says. "My son-in-law is named Christopher - " she says this sweetly and in a pace so unhurried that it can only have been a choice, a choice made long, long ago that she could never now reverse - "and he's such a wonderful boy that if you're anything like him, I would have given you the room for free." She pauses for an eternity during which it is nevertheless clear that there is another thought coming. "I ought to give you the room for free anyway." She does not do so.

The room is in a little pre-fab building across the parking lot, and it's bone cold, with an ancient heater that promises plenty of carbon monoxide if it by some miracle doesn't burn the place down. A bible is sitting on the side table, relieving me of any worries that I've committed a faux pas by not taking one from the stack in the office.

The bed functions, though. In the morning, the shower functions, mostly. I check out and head down the road to a place that the sweet, slow woman claims has the best breakfasts.

It does not. It's attached to a Sinclair gas station, and it has an adequate breakfast with weak bacon and service whose forgetfulness strikes me as a form of hostility. I read the paper from Great Falls, where there is so little local sports news that the agate page lists transactions in professional lacrosse.

It does not. It's attached to a Sinclair gas station, and it has an adequate breakfast with weak bacon and service whose forgetfulness strikes me as a form of hostility. I read the paper from Great Falls, where there is so little local sports news that the agate page lists transactions in professional lacrosse.

There's a phone outside, and I call the 52nd Street Project and talk to Carol, whose reaction to my whereabouts in Hungry Horse can best be described as amusement devoid of envy.

I talk to Reggie for the first time in a few days. I'm told that everyone is asking about me. They want to know what I'm doing out here. Am I finding myself?

I don't answer this. I'm not sure he's looking for an answer, but I don't answer partly because I react to the question the same way I react to the service at the cafe in the Sinclair station, which itself is probably because I don't have any idea what the answer to that question is. I'm in this wide spot in the road in Montana because for as long as I can remember I've wanted to start driving west and just keep going until I hit an ocean. I'm here because I was called here. Or I'm here because I had cousins one place, and then another place, and then way led on to way, and I spent too long on the Swiftcurrent Trail, and Jack Torrance's idiot half-twin answered the door at the first motel.

This hasn't at all been what I expected it to be, except that I keep feeling feeling obedient to some strange spell urging me onward. And all I can tell you is that maybe I'm driving across the country to find out why I've always wanted to drive across the country. Get your own damn Hungry Horse.

That's what I remember feeling anyway. Back here at the Flying Saucer, I might be remembering it wrong.

My intent is to find a hotel near West Glacier, which is a commercial center of sorts just outside the park itself, the better not to be whizzing past scenery in the dark. I pass a billboard for a brand new Super 8 a little further down the road, and after a day of hiking after a night of camping, itself preceded by a night in the Element, and no showers in between, a brand new Super 8 hotel sounds pretty good. But the clerk at the Super 8 gives fairly sneers at me when I ask if there are rooms. So I turn around and drive back to a town called Hungry Horse.

I hate to disillusion you, but Hungry Horse is not quite as charming and rustic as you or I would like it to be. It is, in truth, surrounded by spectacular pine forests covering steep mountainsides. No wooden sidewalks are to be found, however, and although there are saloons they do not seem to have piano players and dancing girls in petticoats. No gunfights break out on the main street , which is also the only street, while I am there, and I see no horses, whether hungry or fully satisfied. In fact, this pretty much sums up what I see in Hungry Horse, except that I do not see the Tamarack Lodge, and I end up driving across the town line into Coram to spend the night.

In Coram I pull up to one little motel and ring the bell, and when the clerk comes to the door he reminds me of Jack Nicholson in "The Shining," only without the mustache and all that mental stability. So when he says "Just a minute," I decide to use the time wisely by getting back in the car and driving rapidly out of the parking lot and up to the next little set of tourist cabins up the road.

In Coram I pull up to one little motel and ring the bell, and when the clerk comes to the door he reminds me of Jack Nicholson in "The Shining," only without the mustache and all that mental stability. So when he says "Just a minute," I decide to use the time wisely by getting back in the car and driving rapidly out of the parking lot and up to the next little set of tourist cabins up the road.The door there is opened by a woman so impossibly sweet and slow that I realize I've locked myself into this place before the words "Do you have any rooms?" can come out of my mouth. She does have rooms, and invites me into a tiny reception area, lit by one table lamp, where every inch of wall space and flat surface overflows with Christian imagery or iconography or proselytizing pamphlets. It takes her about a minute and a half to find the registration form and enter the date, during which time I study the stack of bibles on the counter. Am I meant to take one with me back to my room? Will she tell me to be sure to take one? Will there be trouble if I don't?

She asks for my identification and credit card, and I hand her my license, and she comments of course on how far from home I am. She also notes that my name is Christopher. "What a nice name," she says. "My son-in-law is named Christopher - " she says this sweetly and in a pace so unhurried that it can only have been a choice, a choice made long, long ago that she could never now reverse - "and he's such a wonderful boy that if you're anything like him, I would have given you the room for free." She pauses for an eternity during which it is nevertheless clear that there is another thought coming. "I ought to give you the room for free anyway." She does not do so.

The room is in a little pre-fab building across the parking lot, and it's bone cold, with an ancient heater that promises plenty of carbon monoxide if it by some miracle doesn't burn the place down. A bible is sitting on the side table, relieving me of any worries that I've committed a faux pas by not taking one from the stack in the office.

The bed functions, though. In the morning, the shower functions, mostly. I check out and head down the road to a place that the sweet, slow woman claims has the best breakfasts.

It does not. It's attached to a Sinclair gas station, and it has an adequate breakfast with weak bacon and service whose forgetfulness strikes me as a form of hostility. I read the paper from Great Falls, where there is so little local sports news that the agate page lists transactions in professional lacrosse.

It does not. It's attached to a Sinclair gas station, and it has an adequate breakfast with weak bacon and service whose forgetfulness strikes me as a form of hostility. I read the paper from Great Falls, where there is so little local sports news that the agate page lists transactions in professional lacrosse.There's a phone outside, and I call the 52nd Street Project and talk to Carol, whose reaction to my whereabouts in Hungry Horse can best be described as amusement devoid of envy.

I talk to Reggie for the first time in a few days. I'm told that everyone is asking about me. They want to know what I'm doing out here. Am I finding myself?

I don't answer this. I'm not sure he's looking for an answer, but I don't answer partly because I react to the question the same way I react to the service at the cafe in the Sinclair station, which itself is probably because I don't have any idea what the answer to that question is. I'm in this wide spot in the road in Montana because for as long as I can remember I've wanted to start driving west and just keep going until I hit an ocean. I'm here because I was called here. Or I'm here because I had cousins one place, and then another place, and then way led on to way, and I spent too long on the Swiftcurrent Trail, and Jack Torrance's idiot half-twin answered the door at the first motel.

This hasn't at all been what I expected it to be, except that I keep feeling feeling obedient to some strange spell urging me onward. And all I can tell you is that maybe I'm driving across the country to find out why I've always wanted to drive across the country. Get your own damn Hungry Horse.

That's what I remember feeling anyway. Back here at the Flying Saucer, I might be remembering it wrong.

Friday, February 02, 2007

Going to the Sun

There are a couple of routes to Missoula, my destination, from the east side of Glacier. One of them takes me back to my old friend US 2 near Browning and down around the biggest of the mountains. The other one, which I opt for, and which is nominally more direct, goes right up over the continental divide through the middle of the National Park.

There are a couple of routes to Missoula, my destination, from the east side of Glacier. One of them takes me back to my old friend US 2 near Browning and down around the biggest of the mountains. The other one, which I opt for, and which is nominally more direct, goes right up over the continental divide through the middle of the National Park.The road is called the "Going-to-the-Sun Road," after the Going-to-the-Sun-Mountain, which may or may not come from a Blackfeet name or at least Blackfeet history. Or maybe not; who knows what to believe? It was built in the twenties and thirties, and was and remains an undeniable feat of engineering: 50 miles up and down and through the sides of mountains.

The 50-mile drive ought to take a full day; a full week, maybe. But I've gotten a late start, of course, thanks to hiking, and huckleberry pie before it, and so here I am with encroaching dark, balancing, as from the beginning, keeping moving against nothing better than this.

The highway starts out by winding along the edge of St. Mary Lake, which I mention mostly in order to correct an egregious geographical error made, and subsequently compounded, in the previous posting. The St. Mary River and its various lakes, and more particularly its tributary Swiftcurrent Creek, do not empty into the Missouri. They flow northerly, instead, through Canada and eventually leading to Hudson Bay. I should have remembered this, or at least considered that the river was unlikely to make the couple-thousand-foot climb over the St. Mary Ridge that the Element and I had made on the way to meeting it.

And now I'll shut up for a few moments and let the pictures do the heavy lifting:

Those glaciers, by the way: the National Park Service says they'll be gone by 2030. I'm in no position to say this, having pumped five or six thousand miles worth of carbons into the atmosphere just to get here and take these pictures, and by myself yet. But it might be time to do something.

All these mountains have names, but I have no idea which is which, and couldn't possibly figure them out from comparing my pictures to the map. There's a picture of Going-to-the-Sun Mountain here, and maybe you can figure out if I've taken a picture of it.

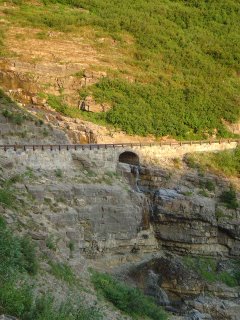

A couple more going up the east side, including one to indicate what the highway is starting to look like, in case you thought it looked a little prosaic in the earlier photo:

At the top I reach Logan Pass, elevation 6,646', and the continental divide. And zip right past it, before immediately realizing that this surely represents a landmark on this trip, one of the biggies, on a par with perhaps only with setting out from Brooklyn and crossing the Mississippi. So I prepare to stop and mark the occasion.

At the top I reach Logan Pass, elevation 6,646', and the continental divide. And zip right past it, before immediately realizing that this surely represents a landmark on this trip, one of the biggies, on a par with perhaps only with setting out from Brooklyn and crossing the Mississippi. So I prepare to stop and mark the occasion.But before doing so, I look up and see that the main reason people are stopping is not the great divide, but a herd of mountain goats blithely wandering around at the side of the road. I won't tell you you can walk right up to them, but you can get pretty close, and kids are running around and screaming pretty much the way I did when encountering that moose. But the goats pretty much mind their own business, like this:

There's another bunch of them across the gap - you can see a few dots representing them in the picture above, just below the big bunch of dark green trees - and at one point a little girl runs up to me and yells, "One of them just jumped all the way from up there to down there - and he didn't die!" And that pretty much sums it up better than I can.

I go back up to the top of the pass and get my picture taken by the sign, and then take a few more so I can show you one that's not disfigured by the guy in the orange jacket:

And then, after a goat dubiously sizes up the Element's mountain-going capabilities ...

... we're on our way down the other side:

I'm cursing myself at this point for having stayed so long on the Swiftcurrent Trail this morning, because dark is fast approaching, the way it does here, and have neither the desire to miss the scenery nor to test my skills driving this road in the dark, and I'm therefore pressing on, as ever, much faster than I would otherwise choose.

I'm cursing myself at this point for having stayed so long on the Swiftcurrent Trail this morning, because dark is fast approaching, the way it does here, and have neither the desire to miss the scenery nor to test my skills driving this road in the dark, and I'm therefore pressing on, as ever, much faster than I would otherwise choose.(Which

isn't all that fast, thanks to both the demands of the highway and the frequency of places to pull off the road and gape. I did stop the car to take this one, by the way.)

isn't all that fast, thanks to both the demands of the highway and the frequency of places to pull off the road and gape. I did stop the car to take this one, by the way.) But there were reasons to stay on the trail as long as I did, of course, and it turns out there are rewards to having done so, as well, and whether or not it's what I had been planning on and hoping for, the only sensible course of action is to be delighted at the way things turned out. Which in this case, is that I suddenly find myself driving down the west side of the Logan Pass at the magic hour.

But there were reasons to stay on the trail as long as I did, of course, and it turns out there are rewards to having done so, as well, and whether or not it's what I had been planning on and hoping for, the only sensible course of action is to be delighted at the way things turned out. Which in this case, is that I suddenly find myself driving down the west side of the Logan Pass at the magic hour.I've lamented my ability to capture the Rockies in the little three-inch by four-inch box I'm carrying around. And these don't come all that close, either. And I claim nothing other than being at the right place at the right time. I'm pretty happy with how they came out, though.

The road winds by a formation called the Weeping Wall, which by the middle of August is reduced to a few trickles here and there, and around "the loop," and as we dip lower into the valley, which on this side drains into McDonald Creek and Lake McDonald, the fading light fills me with sweet sorrow.

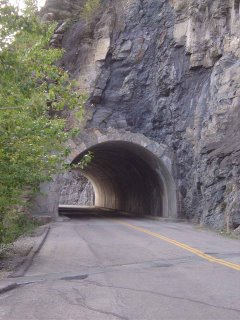

The road winds by a formation called the Weeping Wall, which by the middle of August is reduced to a few trickles here and there, and around "the loop," and as we dip lower into the valley, which on this side drains into McDonald Creek and Lake McDonald, the fading light fills me with sweet sorrow.At one point the road travels through a tunnel, and in the middle of the tunnel there's a little doorway they've cut through the rock so you can go out on a ledge and take in the view. I park on the far side of the tunnel and walk back to see what there is to see. It's kind of corny, and I feel dumb stopping to do this, and then dumb and conspicuous when a minivan pulls up and everybody inside piles out to do the same.

It's an older man with long gray hair and a tie-dye shirt, along with three boys. The oldest of them is about eight, and I take the man to be their grandfather. He speaks softly, and that's the right word: not just quiet but gentle. The kids don't really follow his example, but he keeps patiently pointing things out to them and shepherding them along.

It's an older man with long gray hair and a tie-dye shirt, along with three boys. The oldest of them is about eight, and I take the man to be their grandfather. He speaks softly, and that's the right word: not just quiet but gentle. The kids don't really follow his example, but he keeps patiently pointing things out to them and shepherding them along.They're looking down over the ledge at some mountain goats, about thirty feet below, and they shout and point and occasionally toss a rock over, while their tie-dyed grandfather patiently tries to calm the shouting and rock-tossing. They point the goats out to me, and I'm happy to be included for a minute. Then I walk over to the other corner of the little terrace, and look down, and see something else moving. I stupidly think it's some sort of a black mountain goat, and call over to the boys "Here, come look at this guy." The words are still coming out of my mouth when I realize it's not a mountain goat but a bear.

It's hard to get a good view of it - we're thirty feet up, after all, and the light is dim, and the bear doesn't seem to share the mountain goats' unconcern at being looked at. And it's small - so small that I assume it's just a cub, but the man tells me that that's about how big adult black bears are. "Is this your first bear?" the man asks me, and I don't really need to answer.

It's hard to get a good view of it - we're thirty feet up, after all, and the light is dim, and the bear doesn't seem to share the mountain goats' unconcern at being looked at. And it's small - so small that I assume it's just a cub, but the man tells me that that's about how big adult black bears are. "Is this your first bear?" the man asks me, and I don't really need to answer.I take a picture, and the flash scares it back into the trees a bit. We watch a little while longer, and then pile back into our respective cars, and spend the next half-hour or so playing leapfrog down the rest of the road with darkness falling all about us.

It's night by the time I get to the little village at the upper end of Lake McDonald, where there's a terrible-looking restaurant and a store where I get a crummy little pre-packaged sandwich instead. And a huckleberry cream soda, which almost makes up for the sandwich. I find a phone and leave a message for Dave to tell him I won't be making it to Missoula tonight, and it's a good thing he didn't save a ticket to the Nickel Creek concert for me. And then drive off, along the banks of the lake, under the light of the moon.

Thursday, January 04, 2007

The Swiftcurrent Trail

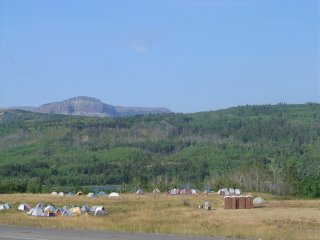

I head back up the road to re-enter Glacier National Park at a place called Many Glacier. On the way there I pass the fire camp, at the north end of Lower Saint Mary Lake. There are little plumes of smoke rising up here and there among the trees, and no particular end in sight for the guys fighting them, and the shantytown they're living in for the duration does nothing to make the job seem more romantic.

I head back up the road to re-enter Glacier National Park at a place called Many Glacier. On the way there I pass the fire camp, at the north end of Lower Saint Mary Lake. There are little plumes of smoke rising up here and there among the trees, and no particular end in sight for the guys fighting them, and the shantytown they're living in for the duration does nothing to make the job seem more romantic.At the park entrance I upgrade my week-long pass to an annual pass for another handful of money. Rand McNally's showing me lots of parks to see out here, even if the calendar's not showing me many days to do it in.

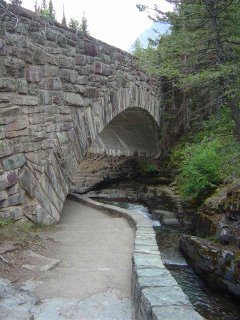

The road to the trailhead runs alongside Swiftcurrent Creek, which I'm telling you mostly to get the name "Swiftcurrent Creek" into the blog. Here's a picture of it:

...which I wish were better. And I will tell you now, so you're not disappointed a few lines from now, that although I've been totally delighted with the camera John lent me this summer, Glacier National Park immediately brought it, or me, or the both of us, to our knees. I'm just not up to capturing its - well, choose your trite expression: glory, grandeur, immensity, majesty, all of the above. Maybe nobody is. North Dakota I loved, but I will tell you that if you're not up to the drive you can rely on my pictures to fill you in. Glacier, you pretty much have to see for yourself.

And I will also tell you now that I had written an earlier version of this, which was summarily lost when the wi-fi connection failed at a trendier but less blogging-friendly coffeehouse, and which was, I feel certain, far more poetic and insightful than this that you're reading now. What can I say? We all of us live subject to fate, and chance, and circumstance, and the best we can do is to try to live our lives in such a way to make those things work in our favor. Which just means I have to try to do my best work now.

And while I'm digressing, to Kathy: This is the first day of the new schedule. And welcome home.

Driving alongside Swiftcurrent Creek, you pass one of those grand old hotels that dot the national parks of the West; I'm feeling behind this morning, owing to my stop for conversation and huckleberry pie, and so all you get is a distant snap of the exterior. I'm sure it's nice, and even if it's ordinary the view out your window isn't likely to be.

Driving alongside Swiftcurrent Creek, you pass one of those grand old hotels that dot the national parks of the West; I'm feeling behind this morning, owing to my stop for conversation and huckleberry pie, and so all you get is a distant snap of the exterior. I'm sure it's nice, and even if it's ordinary the view out your window isn't likely to be.

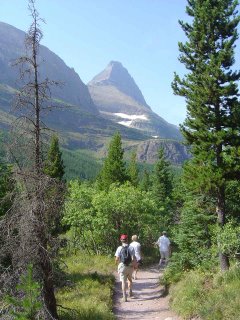

I finally park by the trailhead, where I find a phone and call cousin Dave to advise him of my schedule; I'm expecting to be in Missoula by late in the evening, I tell him. We talk about trails to hike, and he recommends the Swiftcurrent Trail, which travels along a chain of lakes and affords a decent chance of seeing moose. The park guide informs me that I stand little chance of finding solitude there, but, well, bears. That might not be a bad thing. Just in case, I stop in to ask the friendly park ranger. I'm hiking alone, I tell him; should I really sing and talk and annoy my fellow hikers? Annoy away, he says. I leave a note and a map of my route in the Element, pull on my boots and pack a bag with gorp and water, and head up the trail.

I'll spare you endless narration and assume that even my pictures are worth some hundreds of words:

(Do me a favor, by the way, and at least click on the images and look at them full-size. They're slightly less inadequate that way.)

(Do me a favor, by the way, and at least click on the images and look at them full-size. They're slightly less inadequate that way.)After a few miles, I get to the point where the time of day, as well as probably my stamina, dictate that I really ought to be turning around. I have lunch on a rock beside one of the streams that become Swiftcurrent Creek, and St. Mary Lake, and eventually the Missouri, I suppose, and try to determine the best course of action from the Park Service's utterly lame map. But there's really not much worth debating, 'cuz I'm at the foot of an immense chunk of rock that's demanding to be climbed.

So up I go. And am rewarded with this:

And then the trail starts looking like this:

... and since the aforementioned lame map gives no reliable indication of whether it's half a mile or four miles to the top of the cliff, I decide it's time to start heading downward.

I meet lots of nice people along the way, which is good because it allows me to stop singing "The Happy Wanderer" over and over again and have some conversations. (Before I go hiking in the Rockies again, incidentally, I'm going to learn more than the first verse. And by the way, you'd think there would be a little more consensus about what the lyrics are, even in translation. And that the world could decide whether it's "Val-deri" or "Val-da-ree" or "Falleri," for which you'd think the original German would suffice. It's also worth reading the Wikipedia entry to learn that the Montreal Expos played "The Happy Wanderer" to celebrate offensive explosions, while their fans sang along. This perhaps goes a long way to explaining why there is now baseball in Washington.)

So anyway, those nice people. I meet them. There's a big group near the top of the cliff, or at least as close to the top of the cliff as I get, and they lend me their binoculars to look at the mountain goats and bighorn sheep in the picture here. See them? If you zoom in about 12 times you'll notice some white pixels, just to the left of that big cleft toward the left side of the picture, that I think are the sheep.

So anyway, those nice people. I meet them. There's a big group near the top of the cliff, or at least as close to the top of the cliff as I get, and they lend me their binoculars to look at the mountain goats and bighorn sheep in the picture here. See them? If you zoom in about 12 times you'll notice some white pixels, just to the left of that big cleft toward the left side of the picture, that I think are the sheep.The nice people commiserate with me as I do what I can with first aid tape to repair my shoes, which have suffered a blowout structural failure in an inconvenient location.

And another couple and I stop when we reach the proper altitude and pick a few huckleberries that the bears have missed, and maybe I'm in need of an energy boost or maybe they're just good. And I meet a German couple, who are not singing "The Happy Wanderer," national heritage be damned, but they're quite pleased that I stopped to pick up her flip-flop on the way up. We pause, at an absurd altitude where I have to rest every fifty paces or so, and try to decipher the damned map and gauge the hours of sunlight left and figure how many more switchbacks there are 'til things level off.

This is as close to the source of the Missouri as I get today. They keep on at least a few more turns, but I head back down.

This is as close to the source of the Missouri as I get today. They keep on at least a few more turns, but I head back down.On the way down I meet a ground squirrel, which is not a bighorn sheep, it is true, but is somewhat more visible:

Back on level ground, or anyway more nearly level ground, I bump my way back trying not to think about how many hours it took me to get to that particular tree. An older couple are looking through glasses at a moose, walking along one of the lakes, and let me have a look. He scolds me, in a grunty mumble, for not being able to find it quickly enough. While I'm searching, and finally find it, he feeds nuts to a squirrel and scolds it for not being grateful enough. "Now come on, that's a perfectly good almond there," he grunts, sounding, and looking, so much like Jack Germond that it occurs to be that maybe this is what Jack Germond is doing in his retirement. Although it then occurs to me that Jack Germond doesn't really have the physique to go on six- or eight-mile hikes at altitude.

My direction of travel brings me closer to the moose, and rounding a corner I get a clear view of it. When I was six or seven years old, my family did an overnight hike in the Tetons, and on a rainy August morning in a place called Cascade Canyon, my brother and I came through some trees, not singing German children's songs, and almost ran into the hindquarters of an immense moose smack in the middle of the trail. Of course, most moose are immense to a kid that age, I suppose. Being six and eight, or seven and nine, whatever, we commenced to hollering, and ran off to scream to everybody else what there was to see just ahead, with predictable effect on the object of our interest. Everybody else was pretty excited at seeing an immense moose a mere twenty or thirty yards away, while Will and I expended considerable energy to convince them of how much more big and close it had beenand I tried to ignore the knowledge that I'd blown it in my excitement. I think every minute I've spent in a place like Glacier has been an effort to find that moose straddling the trail again. And today I consider that if you see a moose from even a quarter mile away, you'd better take the picture, because you might not get a better chance.

My direction of travel brings me closer to the moose, and rounding a corner I get a clear view of it. When I was six or seven years old, my family did an overnight hike in the Tetons, and on a rainy August morning in a place called Cascade Canyon, my brother and I came through some trees, not singing German children's songs, and almost ran into the hindquarters of an immense moose smack in the middle of the trail. Of course, most moose are immense to a kid that age, I suppose. Being six and eight, or seven and nine, whatever, we commenced to hollering, and ran off to scream to everybody else what there was to see just ahead, with predictable effect on the object of our interest. Everybody else was pretty excited at seeing an immense moose a mere twenty or thirty yards away, while Will and I expended considerable energy to convince them of how much more big and close it had beenand I tried to ignore the knowledge that I'd blown it in my excitement. I think every minute I've spent in a place like Glacier has been an effort to find that moose straddling the trail again. And today I consider that if you see a moose from even a quarter mile away, you'd better take the picture, because you might not get a better chance.Today, though, I'm lucky. The moose viewing gets better and better, and I follow the little spur off the trail that leads down to the edge of the lake, and right there are momma and poppa and little baby moose.

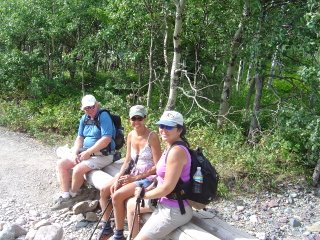

A trio of folks, one of them from Albuquerque, accompany me most of the way back. There's considerable talk among the crowds on the trail - and "crowds" is a bit much, but there are definitely favored resting points where ten or fifteen people will be gathered - of a grizzly that crossed at the falls a few minutes earlier.

A trio of folks, one of them from Albuquerque, accompany me most of the way back. There's considerable talk among the crowds on the trail - and "crowds" is a bit much, but there are definitely favored resting points where ten or fifteen people will be gathered - of a grizzly that crossed at the falls a few minutes earlier.The photographer among the trio dismisses the likelihood that it was a grizzly; probably just a black bear. He's local, and spends a lot of his time on the trails, and carries a camera roughly the size of a Navy vessel's anti-aircraft gun. He's seen a lot of grizzlies, and can afford not to be disappointed at this missed opportunity than I can.

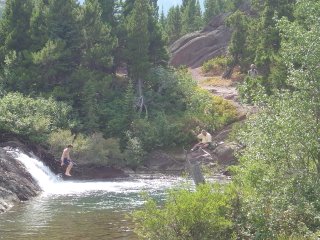

We wait a bit by the falls, and watch a kid undeterred by really cold water, but the grizzly, if it was one, is done with photo ops for the day. So after a while we head on down the trail, and after another while we reach the point where my pace and theirs diverge, and the woman from Albuquerque and I make the "next time you're in" sort of promises, with no real way of following through on them.

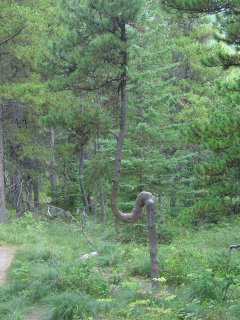

We wait a bit by the falls, and watch a kid undeterred by really cold water, but the grizzly, if it was one, is done with photo ops for the day. So after a while we head on down the trail, and after another while we reach the point where my pace and theirs diverge, and the woman from Albuquerque and I make the "next time you're in" sort of promises, with no real way of following through on them. Finally the pines turn to birches, and I pass a memorably indecisive tree, and I find myself back in the paved part of paradise. The Element is patiently waiting for me where I left it, and never before on this trip have we been so glad to see each other. There's no pass over the ridge up this canyon - none other than the one I turned away from, at least - so we head back out to the main road, traveling along the banks of Swiftcurrent Creek one more time.

Finally the pines turn to birches, and I pass a memorably indecisive tree, and I find myself back in the paved part of paradise. The Element is patiently waiting for me where I left it, and never before on this trip have we been so glad to see each other. There's no pass over the ridge up this canyon - none other than the one I turned away from, at least - so we head back out to the main road, traveling along the banks of Swiftcurrent Creek one more time.